The Dignity of All Work

We often undervalue the contributions of our nation’s workers. Instead, we must value and celebrate the dignity of all honest work.

There is much talk in the media these days about the thousands of jobs in British Columbia and the rest of Canada that will have to be filled by non-Canadians – meaning new immigrants and/or temporary foreign workers. Most of these jobs will require workers with trades skills, technical experience and knowledge. While this may be the case, the tone of the public discourse is, perhaps unintentionally, diminishing the value of the kind of work that many Canadians, new immigrants and temporary foreign workers do.

When their jobs are called “menial,” “grunt,” “low skilled,” or “unskilled,” I believe we are unfairly degrading this kind of work. Our society cannot function without people working in these jobs, and the people that do them deserve to be valued for their contributions to our communities.

In Canada, we don’t only need people working in high tech, “high skilled” jobs. We need people to work in all aspects of a functioning society. Whether it is picking the food that ends up on our kitchen tables, serving coffee, building houses, or growing a business, each person contributes to the development of our communities and our economy in an important way. Each position that a worker takes on will help them to develop the skills they need to progress in their own life and to further advance our economy as a whole. And each position allows a worker to develop important people skills such as communication and teamwork, ensuring more cohesive and harmonious communities.

My father came to Canada in 1960 with no marketable or technical skills. He worked as a labourer in a saw mill, a plywood mill, and in a small metal fabricating shop on the weekends where he painted railings. Eventually he started his own construction company. He became successful in the latter and ended up pioneering one of the first Canada-India partnerships, building a major education and health care centre in India, and forging a relationship with the University of British Columbia in training nurses. This initiative has been beneficial to both Canada and India, and may not have been possible if it weren’t for the skills my father had learned in his earlier roles.

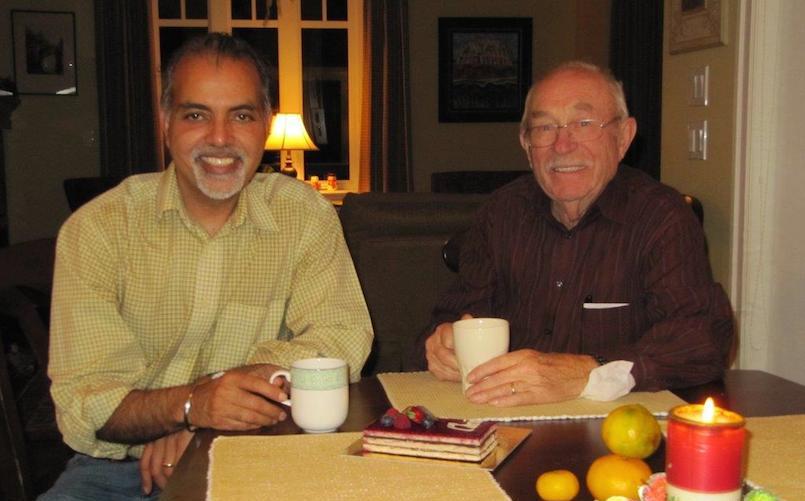

Similarly, my father-in-law, Jacob Loewen, and his family arrived in Canada in 1948 after fleeing their home town of Tiege, Ukraine in 1944, which had been under communist rule. With a grade eight education and a short apprenticeship in carpentry in Germany after the end of World War II, his first job was on a farm in Abbotsford. Later, in 1951, he worked on some construction sites in Kitimat and Burns Lake, and in 1956, he started his own construction company, going on to build over 125 single family homes in Vancouver and multiple commercial buildings over a 25 year period. He worked hard from sunrise to sunset for many years and he loved every minute of it. He even found time to take English literature classes in the evening at John Oliver Secondary School and the Dale Carnegie Course to improve his English and public speaking skills.

My mother-in-law, Hilda (Stobbe) Loewen, whose family also came to Canada after World War II says, “….in Canada we were no longer afraid. We could now work hard and create a better life for ourselves and others.”

I started working when I was 11 years old; I took on all kinds of jobs around Port Alberni where my family had immigrated. My first job was picking potatoes in September with my mother and my youngest sister. I later delivered the Vancouver Sun and Province newspapers, worked in a hardware store, picked strawberries, corn and vegetables on farms, and worked at the plywood mill. In the summer after grade 10, I was working 16 hour days – on a farm seven days a week, and nights at the Alberni Plywood mill.

When we moved to Vancouver South, I began working after school and on weekends at the Terminal Saw Mill and later one summer at the Eburne Saw Mill where the B.C. Transit Station now sits. I worked on the log boom, on the green chain, as a carpenter’s helper, on night fire watch and on cleanup crew. Many evenings and weekends I would also help on my father’s construction sites while at school and university.

Most of these jobs would be classified as “menial and low-skilled.” But at each of those jobs, I learned something new and I brought that knowledge and skill with me to the next job. I learned technical skills as well as people skills, and how to work as part of a team. I learned firsthand the strength and dedication it takes to do manual labour and to work the land, efforts that are essential for thriving communities.

Like my father and my father-in-law, I also gained an understanding about constructing homes and buildings which has been the foundation of my success in business later in life. Without the knowledge gained in earlier roles, the three of us may never have been able to grow our businesses, let alone participate in the various education, healthcare, and community building projects we have been involved in.

When we use words like “menial” and “unskilled”, we undervalue the important and necessary contributions of our nation’s workers. Without these positions, our country would not thrive. We must value all work as an important element to the growth of our society and economy. Maimonides, a preeminent medieval philosopher, once said: “The greatest gift that we can give one another is the gift of work.”

Let us accept this gift with grace and humility. Let us celebrate the dignity of all honest work.

News: Barj Dhahan on business and spirituality

Vancouver entrepreneur Barj Dhahan has found success in business; satisfaction in spirituality.

“I feel fortunate in who I am. My life has been one of … exploration of ideas, incorporation of different thoughts, leading to a greater sense of self-discovery,” he says.

When he was 10, Dhahan, his mother and three of his four sisters left his family’s ancestral farm in the Punjab region of India to join his father in Port Alberni on Vancouver Island.

Budh Singh Dhahan had already been in Canada for almost a decade, working in the lumber industry. He was “very entrepreneurial,” Dhahan says of his dad, who later moved into home construction in Metro Vancouver.

The father’s go-for-it attitude rubbed off on his son. At 57, Dhahan is president of the Sandhurst Group of companies, which specializes in Tim Horton’s outlets, Esso gas stations and commercial real estate development throughout Metro Vancouver and B.C.

However, as much as Dhahan enjoys the challenge of leading a corporation with more than 150 employees, he and his family have probably become best known for their big, imaginative philanthropic ventures.

The Dhahan family’s latest effort led last year to special events in B.C., India and Pakistan, where Dhahan and others announced the world’s first Punjabi-language prize for fiction writing, worth $25,000.

The Dhahan International Punjabi Literary Prize is one of several major non-profit brainstorms of the Dhahan family and the Canada-India Education Society, which they co-founded.

The family’s first major philanthropic project has been a game-changer. It arose in the 1980s when Budh Singh and others helped establish the Guru Nanak Mission Medical and Educational Trust, which now operates a 200-bed hospital in the family’s ancestral village of Dhahan-Kaleran, which is 100 kilometres from the Sikh holy city of Amritsar. In a partnership with the University of B.C. and other organizations, the trust runs an affiliated 1,600-student public school and a program that has graduated about 1,800 nurses and midwives.

During a wide-ranging conversation at the family’s Kerrisdale home, Dhahan said he does not think business should be conducted “to pursue money, but to provide wellness and a good life.”

Even while he explained his route to corporate success, Dhahan emphasized his passion for community, spirituality, the social safety net and the fast changing multicultural experiment that is Canada.

Dhahan is not without criticisms of Canada’s racial past, but he’s grateful for what his family has been able to accomplish here. It was near-despair that drove Dhahan’s father to leave India for Port Alberni in 1959.

It was almost impossible for a decent man at that time to get ahead in the Punjab region of India, Dhahan says. “You either had to be wealthy or crooked. And my father was neither.”

In British Columbia, with its functional economic and political system, Budh Singh had a chance to progress on hard work and merit. As a result, Dhahan doesn’t take for granted Canadians’ general sense of fair play and openness.

The family’s casually elegant home has many architectural features, memorabilia and art, which help highlight some of Dhahan’s values and passions.

Barj and his wife, Rita, believe everyone should integrate fully into Canadian culture. That’s why they intentionally chose not to build a fence around their front yard.

“We must mix and get to know our neighbours. We must cross boundaries,” he says. “In Canada we run the risk of moving into ethnic silos and not talking to each other.”

Dhahan is concerned some newcomers from India and China can now come to Metro Vancouver and spend all of their time within their own ethnic enclaves, without having to inter-connect or learn English.

Another revealing object in the family’s living room is a black-and-white photo of one of Dhahan’s turbaned grandfathers in California in 1923. It shows the family’s roots in both South Asia and North America.

The high-ceilinged entranceway also features an imposing painting of early 19th-century Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh, whom Barj admires for his “remarkable” ability to run an Indian kingdom based on peace, fairness and prosperity.

Also on display is a small painting of an icon of Mary and Jesus as a baby. It was painted by Rita, who was raised in B.C. in a Mennonite family. The icon points to the deep commitment both Rita and Barj show toward their spiritual lives, which blend elements of Sikhism, Christianity, yoga and other traditions.

Before explaining Barj’s views on multiculturalism, spirituality and social values, however, it’s worth highlighting how he became a success in business.

Dhahan and Rita had next to nothing when they married in 1977.

But Dhahan was raised by parents who did not emphasize “leisure” as much as modern-day parents, such as himself. He was taught to work diligently and not expect to have it easy.

While attending multi-ethnic John Oliver high school in east Vancouver, Dhahan helped his father build single-family houses. So he understood business.

He wasn’t exactly clear what his university studies were leading to, however. So he leased a “mom and pop” gas station. It went pretty well. “We’d spruce them up, do some landscaping.” Then he leased another.

While he and Rita raised their three children, Dhahan added some Tim Horton’s franchises, some more gas stations, stepped into commercial real estate construction and began developing convenience and professional centres.

“It all adds up to a little bit of everything,” he says. Dhahan owns three gas stations (at one time he operated seven) and six Tim Horton’s outlets, the latter of which may be the most profitable of his businesses.

Given the national controversy over the high number of temporary foreign workers in Canada, Dhahan readily offers he was “one of the first” in Canada to bring them in to serve his Tim Horton’s customers.

He defends the use of temporary foreign workers (known as TFWs), stressing they are sincere, hard-working people who send much of their money back to places such as the Philippines and should be treated as “human beings, not just TFWs.”

He’s tried to help some immigrate to Canada. He’s all for giving newcomers a chance in this “land of opportunity.”

What Dhahan doesn’t like, however, is people who come to Canada or were born here who mostly take advantage of it, complain and give nothing in return.

He’s disturbed, for instance, about the “exploitive” business practices of some South Asian and Chinese business people in Canada. He says they treat employees of their own national origin harshly, because the staff don’t understand their rights under Canadian labour law.

Dhahan is also bothered by the lack of national pride and loyalty shown by residents of Canada who head across the U.S. border to try to save money on retail purchases.

And he’s decidedly unimpressed by Canadians who whine about paying taxes.

“The two things that are most important about Canada,” he says, “are its social-safety net and universal access to public education and health care.”

Inspired by the legacy of New Democratic Party founders Tommy Douglas and J.S. Woodsworth (both Christian ministers), Dhahan says citizens have to be prepared to pay taxes to take care of “the portion of the population that is challenged.”

Holding on to such values, Dhahan has gradually forged many connections in politics and higher education.

He is well known to Prime Minister Stephen Harper and B.C. Premier Christy Clark (who, with Dhahan, was in India in 2011 to visit the Guru Nanak hospital). He’s often jetting off on government trade missions.

Simon Fraser University professor John Pierce says Dhahan “is promoting change by broadening his entrepreneurial activities to include a rich variety of social, cultural and medical initiatives at home and abroad.”

After meeting long ago through the Canada-India Education Society, Pierce, head of SFU’s environment department, says Dhahan’s business acumen, communication skills and thoughtful approach give him an unusual ability to bridge cultures.

“His unique set of talents, combined with the growing inclusiveness of our political system, make him an ideal candidate for a future leadership role in Canada.”

Dhahan’s resume notes he’s been involved with the Vancouver Quadra Liberal riding association. Does he harbour any political ambitions?

He’s not interested in power, he says, but in “developing policies.”

Far removed from high-flying business, politics and global philanthropy, however, there is another side to Dhahan — the inner life.

Although raised in a Sikh household, he does not regularly attend a gurdwara. As a young adult he was drawn to Christianity. He obtained a diploma in 1985 from Regent College, an evangelical school on the UBC campus.

But he’s shifted since then. In 2009 he obtained a yoga-teaching certificate from Langara College. And now his living room is peppered with eclectic spiritual books such as The Essential Mystics, by Andrew Harvey.

Dhahan and Rita don’t belong to any religious organization, but find guidance in the inter-spiritual teachings of people like the Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, particularly in his book, Living Buddha, Living Christ.

Since Dhahan is highly aware of his multifarious ethnic, national, professional and spiritual identities, he also makes clear: “I’m a big promoter of multilingualism.”

Speaking English and Punjabi, as well as some Hindi and French, he would like to see every Canadian become fluent in both English and French (“since they bind us as a nation”), plus a third language.

His ambitious dream of a more multilingual Canada is one reason Dhahan felt compelled to create the Dhahan International Punjabi Literary Prize. He wanted to display more loyalty to both his mother (who remains more comfortable in Punjabi) and his “mother tongue.”

Canada has 650,000 people who speak Punjabi, he says, with 200,000 of them in B.C.

Dhahan would like to see the literature prize, which will be awarded for the first time in 2014, build more bridges. Prize recipients will have their book translated into English.

Going further, Dhahan even wonders whether the literature prize could build bridges between the often-hostile residents of Indian and Pakistan, who make up most of the 100 million people who speak Punjabi.

His voice fills with hope as he says: “One consul-general told me, ‘Maybe this prize will help bring India and Pakistan together.’”